The Cooper's Hill Cheese Race

2023 · 12 · 29

There were reporters from Norway, Australia, Japan, and Brazil, but they all asked: Why? Why not just buy some cheese at the store? Why chase a wheel of double Gloucester that, given its aerodynamic properties and one second head start, you would have no hope of catching?

They all reveled in missing the point of the event, which was simply that: The hill is steep, so I will run down it. Back in the depths of heroic time, when some peasant farmer conceived of a race down Cooper's Hill as a way to sort out the local grazing rights, he was simply mythologizing what he would have been doing anyways. The cheese was always an excuse, never a motivation.

The train through the Cotswolds was full of American families delighted by everything. "Susie, do you see that stone wall? Susie, put your phone down; there's a vine climbing up the wall."

I got off ten miles early, drawn from the train by the intricate shadow cast by a brick clocktower. As I climbed out of Stroud, the road rose sharply between hedges that caught and toyed with the light like sea glass. Sign posts announced village names that could change your life—The Vatch, Birdlip, Slad—and the occasional shaft in the foliage seemed to open straight down, revealing regions entirely alienated from the sky - slick dark embankments that ended at riverside paths, dense with ivy a hundred feet below.

In Painswick, a narrow green belt cut across the side of a hill with small hedgerows opening into back gardens like corridors in a maze. I followed the only person I saw, an old woman in a gauzy aquamarine shift who was always just around the next bend. Eventually she disappeared between the fused topiary of a spare and dusty churchyard. There is always a sense of having missed by three to four decades the English Village you spent your childhood desiring, and of finding in its place a highly self conscious replica. The pubs are 16th century receptacles for a fussy Victorian sentimentality: sticky toffee pudding, triple cooked chips, that desperate Windsorite love of the twee trio. There are no priests solving murders. Somewhere on the dozen lavish pages of the menu is an admission, hidden under a typographical flourish, of ownership by a holdings company in London.

The first visitation came in Brockworth—the sort of English town that you are not told about abroad. Stepping out of a Co-Op with two bags of apples and peanut butter, I saw Cooper's Hill ascend like a heavenly ski ramp and ran the final mile through back lanes and open fields.

The hill was framed on two sides by dense forest, cordoned off on all four with an orange plastic mesh. I made my way up the center, surprised at how hard it was to keep from toppling backward even at a crawl, and five minutes later took my first look down beside an elegant couple who had flown that day from Tokyo. It was 600 feet long and as wide as a highway: concave to the extent that no photo could capture its grade. To the left, a deep pockmark cratered the slope; to the right, thick clumps of grass had been polished down to a Velodrome smoothness.

More tourists appeared, rekindling a suspicion that certain British events don't come fully into existence until a bunch of Americans and Australians arrive to observe them, shouting as they launch drones and unload cases of beer from the largest cars that can be rented at Heathrow. At the base, a family from DC introduced themselves as political exiles, having fled Trump to Sweden. Now, they said—as if these two events had some intrinsic or causal connection—they had come to see the cheese race. The mom was intensely friendly with no visible pores, recalling my childhood distrust of charter school parents: their scrubbed high definition awakeness and aura of spiritual menace. A Californian couple, early 40s and platinum blonde to their shoulders, administered themselves like the West Coast antidote, referring to me only as "baby!" or "the man".

A dozen of us gathered at the peak, trading tips for the following day and doing practice runs for the Australian and Norwegian TV crews. Starting with a controlled lunar bounding, you quickly discovered that there was no way to slow yourself down, that even when you fell on your back and adhered yourself to the grass in a panic, you were launched like a slalom into a chainlink fence thirty feet beyond the base. I was cautious and got lucky both times—a bit bloodied, a sore wrist—but in the real thing, with nineteen others vying for the same path, I knew I would have to commit.

Just before sunset, the TV crews clotted around the gate. Loping up with a droopy handlebar and tense shoulders came the old master. "That's 23 time winner Chris Anderson," an expository whisper informed us. "He was on the Netflix special."

After a few hesitant handshakes, Chris showed us his technique, which hinged on the incredible elasticity of his hamstrings. Starting with a graceful leap outward, he would run lightly until he lost his footing, drop for a brief slide and then kick back up into his run like a piston, repeating this cycle all the way down—his vertical and horiztonal momentum kept completely separate. He favored a line that ran down the center of the grassier right face. He wanted to be clear: he had run every line, had won the race every way it could be won. This year was dry, so there would be more bad breaks, fewer long slides. We crouched around him and nodded along absurdly, pretending that we could hope to replicate this feat of genetics, the athletic heights achieved in this man's singular Late Style. Above all, he told us, turning to survey his assembled novices sternly: "Avoid the pit." It was a tantalizing shortcut that promised nothing good under race conditions. "There'll be some Japanese kids here tomorrow. Fearless. I was too once. Always go straight in the pit. See how they go."

He announced frequently that he wouldn't be running this year—that it wouldn't be right for his family—but it was obvious that he would. You could see in his eyes that this hill was the epicenter of his life's narrative, the site of a young first victory often revisited in dreams. Fatherhood had only deepened that mystery; the hill still held him in its thrall.

At dusk, everyone cleared off to airbnbs in the Cotswolds except one tent of Swiss teens. I rigged up my hammock between two trunks perched over a sprawling hollowed out root structure. The light in the copse was an evil red, and the back end of each gust sucked my hammock out over a plummeting gully. I tore it all down and dragged it out to a patch of clover that looked out over the lights of the valley.

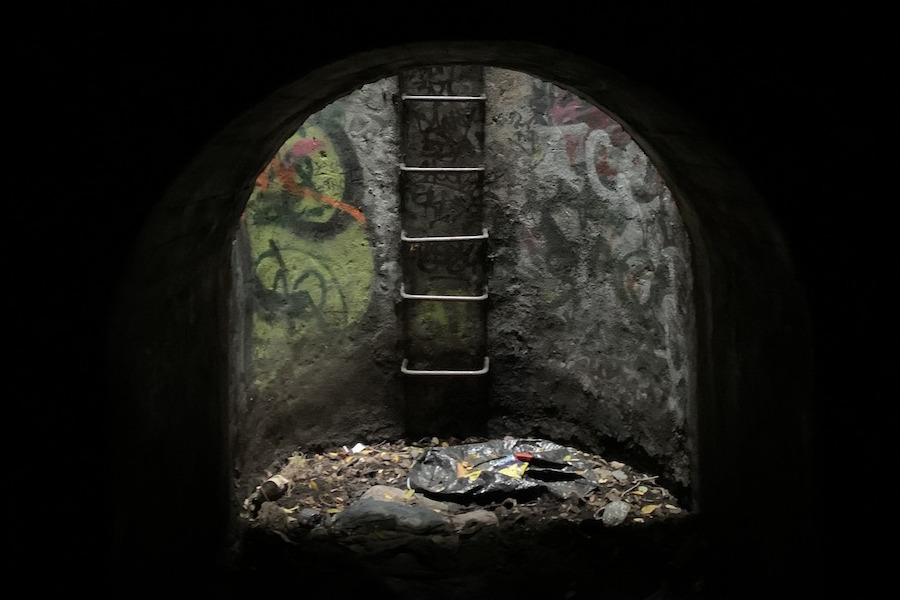

I woke coated in dew some time before 5. An angelic glow flowed up over the edge of Cooper's Hill. I hid my backpack in a dark hollow beneath some roots and walked a few miles to an industrial estate, where I took turns bathing in a Costa sink with a man who lived in his car. On the walk back, I encountered an albino charger in a field of gold.

I returned to a hill transformed: to the first signs of a crowd that would grow to thousands by the morning's end. I found myself anxious to assert a sort of sovereignty over the hilltop, slipping into conversations that I had slept up here. A weathered couple I had befriended the night before, two people glowing with the good luck of having found one another later in life, offered to get my backpack back to London if the race went poorly.

Soon the organizers arrived: gaunt locals with a demented intensity, their track suits dressed up with cheese hats and reflective vests. They emerged from the trees like an army composed only of generals, each more esoteric than the last. Cans of cider spilled out of their backpacks and rolled down the hill as they shouted us into rows and presided aggressively over the gate. They were led by the captain of the local rugby club—boyish from some angles but otherwise scaled up beyond comfort, with a broad slab of brow supporting a twenty gallon hat. He in turn showed deference to the "master of cheese", a man in a white lab coat who jogged lightly across the hill with a short crooked staff that they honored as a village relic.

Of the crowd assembled on the hilltop, a hundred or so stepped forward to compete. We were routed into a sort of chainlink holding pen, where we crouched for nearly two hours, discussing what had led us there. A military pilot named Matt passed around a flask of whiskey. It was almost entirely men under 35, young expeditionary spirits—some gregarious, many brooding and withdrawn. A Canadian bouncer, hairless in a tight green shirt, announced his impending victory and pushed to the front. Sitting silently next to me, a Japanese kid stared hard at whoever spoke as if desperate to decode the movement of their lips. When I asked his strategy, he grinned and pointed to the pit. "Kamikaze."

Leering out from the tree line on either side, the crowd stretched down to the base and spilled out into pastures toward the horizon. A voice on a megaphone announced the arrival of the ominously named "catchers", and the crowd roared as the local rugby club sauntered in to form a line across the bottom. They roared again as a young boy made his way up the hill with the sack of cheese wheels. A dozen streamers circulated behind the chainlink fence, ravenous for content. They all employed a deadpan tempo and some piece of visual novelty, a pair of cyan glasses or a waxed mustache. I rewrapped my toe, broken a week earlier, in a wad of borrowed tissue and decided that I would do everything in my power to avoid cartwheels.

The shared whisky paid off, and the gate warden pulled Matt in for the first heat; I slipped in behind him. 20 of us filed out onto the starting perch, a narrow ledge of dirt just beneath the peak. A red-haired kid of no more than 15 ("From Cooper's Edge, sir," he said pointing to the horizon, "that village there.") made it in behind me.

Enhanced by the waiting period, the valley below seemed impossibly remote: a much lower level of the world flattened into an endless expanse of pastures. The Canadian bouncer leaned precariously out over the edge.

Just before the race, a Japanese reporter was allowed through the gate for formal interviews. Trailing the cord of his mic up to a camera crew twenty feet above, he clung to the grass, terrified of the slope as he crawled slowly from one of us to the next: "Young man, hello. Japan TV. Why?" I felt like the elusive subject of an alpine nature documentary—the crazed figure at the heart of a Herzog film.

The reporter was sent out. The master of ceremonies lifted the wheel of cheese over his head and a low violent chant spread all over the hillside and back into the trees, thousands of voices stretching over a mile away: Cheese. Cheese. Cheese. Cheese. Somehow in that moment the event transcended a bad joke and become something ritualized, ancient, terrifying. Looking out at the faces of the Britons between the trees, I wondered if this was how the first Roman legionaries had felt. I saw that they were here not for novelty but for carnage. As the village elder called out the rules over the chant, I looked over in a trance and saw his enormous deputy in the spangled hat grinning cruelly at us, a moment that haunts me to this day. Then the cheese was lowered and the organizers began their slow count to four. I became acutely aware of the cruel irreversibility of time.

Then: nothing, just motion and the collision of bodies. I recall only one detail from the race itself: a bearded Australian laughing fiercely as he spiraled past me. Then I was cradled in the kind arms of the linebackers—lifted into the light, I thought, much like the cheese had been moments before.

The Canadian bouncer was totaled. He had crossed the hill in a flagrant diagonal, entered the pit, and begun a series of tight inversions that bounced him back across the face to end where I did at about the same time. The first thing I noticed after the catchers hurled me back to earth was his pale placid face very near me as he repeated the phrase "both out and shattered". I looked down and saw that he was referring to the lower half of his leg, which had left its normal mooring and snapped clean in two. Volunteers rushed in with a blanket to block the streamers zooming in on the gore.

I staggered over to clutch at the pilot Matt only to realize that he was mid-interview—and that he was holding the cheese. "Hello, BBC News. I'm sure our viewers would love to know: Why?" I did interviews in three languages, validation of a long period of fruitless hobbies. An Australian sportscaster asked me if I was hurt, so I did an on-air tally. To the broken toe I had added an immobile wrist and ankle; a sheet of blood ran down the backs of my thighs and coated my palms. He asked where it was coming from, but I only smeared it around in dumb perplexed silence while I searched. They didn't use the footage. Then Chris Anderson lost the second men's heat, an unconscious Canadian won the first women's, and we were quickly forgotten.

For the next few hours I meandered up and down the hillside in long slow circles, basking in a minor celebrity. As the later heats of the race grew less serious, the tone of the event somehow darkened. The sun was unbearably intense, but the crowd kept growing. Vans arrived to sell donuts and hamburgers. The forested slopes were covered with people stunned by the heat or crawling up for a better view. I watched an obese family collaborate to pull themselves into the lowest branches of a tree and then lose hold of their daughter, who slid back down and disappeared into the crowd. There were interminable delays between each race: ambulances blocked by ice cream vans, a 20 minute altercation over megaphone between a youtuber who had jumped the fence and the head of the volunteer parademics.

Everyone assembled was so intensely hungry for injuries, which the racers offered in profusion with pops and cracks that echoed out into the fields. In one of the final heats, a young streamer changed his mind just as the cheese was released but was carried forward by his own desperate momentum. He spent the first half of his descent clawing at the hill, and only managed to stop when he broke loose and flew with a horrible wet sound into a narrow outcropping near the bottom. Crumpled against the ledge, he held up his thumb for the crowd, amazed at the new angle it formed with his hand. Thousands of voices let out the same sated groan.

The races ended. I staggered down into the village but couldn't find anyone I knew at the pub. The sun had an immediate acidic effect on anything briefly exposed. The "catchers" lost their shirts and began playing a game that required you to drive your forehead against a brick wall to try to catch a falling pint. As I watched, the deputy conscripted a terrified German with a solid palm on his lower back.

I fled back into the horrific depth and warmth of the pub, eager for a place to wash out my wounds. In a vast carpeted room with blackout curtains, an old projector played a compilation of 2000s pop hits while local children danced frantically beneath a closed mini bar. When I finally found a sink, the water came out so hot that steam filled the small bathroom, and a man I couldn't see growled, suddenly very close to my ear, that I was getting blood on his shoes.

Humor and camaraderie slowly returned on the train back to London, where a long line formed outside the bathroom, a makeshift triage for cheese race injuries. I gave my first aid kit to the Japanese kid and never saw either again.

As I go through these notes six months later, sitting by the Christmas tree in a flooded Californian town, I worry that they might sour or elide the ecstasy of that weekend: how full and round and self sufficient it was—how efficiently it released a drudgery that had held me for months like the cold grip of a vice. The roads will reopen soon, but for now I think fondly of Gloucester and of those who leapt with me down into its endless pastures.