Death Drives in the Aleph

2025 · 02 · 26

"In that single gigantic instant I saw millions of acts both delightful and awful; not one of them occupied the same point in space, without overlapping or transparency... Nonetheless, I'll try to recollect what I can."

For the better part of ten years, terrified of both impermanence and the false eternities of cloud storage, I never backed up my photos.

There were a dozen false starts on dropbox. Empty, meticulously named folders sketched out taxonomies that I thought could contain the world in perfect miniature. I would spend days on these systems and then abandon them as soon as some intrinsic fault or other became clear. Few of them would have been legible to anyone else. None could account for the basic fact that I spent most of my time driving rented cars: the least categorizable activity, filling only the loosest stretches between more defined spaces and periods of life.

It didn’t help that most people I liked couldn’t or wouldn’t drive. Bombing out of the tracks they’d been on at 19, they had scattered to minor but achingly atmospheric cities. I would pick them up with some pretense - the idea of a quest, a great nostalgic return or a new event that seemed to promise a path forward - and then spend weeks driving them around, exchanging so many words that it was as if we were attempting a definitive fusion.

As much as I enjoyed the conversation, I was happiest when they fell asleep in the passenger seat, and I had another six or seven hours to myself just to drive. I could indulge more fully in what I actually wanted: that delicate puppetry of branches playing across the windscreen or parting briefly to reveal a distant swell of moonlit hills. That sense of being outside of time. The space of the cab encloses you from all this with a series of layers: first the tunnel of the headlights like a formal foyer, then the fogged glass and the glow of the dashboard. There are few things more beautiful than those flickering dials mirrored and projected out over the road. At some point your certainty in the biological body begins to fade; the seat no longer seems to press back up against it. These changes are acknowledged with a dreamy indifference. Whatever envelope contains “you” extends through the vinyl and out to the wheels and body, where that low roar of wind and gravel become cognitive defaults rather than additions. This effect is sensitive. Maintaining it for hours requires a unique set of skills. Some foreign cars will still let you turn the headlights off on the highway to inhabit it more fully. Most music breaks it, but the right song seems to expand its boundaries, the music peeling off and applying itself like a thin layer to the landscape. I’ve never understood what people mean by most pop-psychological states - by “dissociation” or "flow" - but if they are achieving this effect outside of a car, I envy them.

These drives occurred over the course of ten years: some little more than a few days apart, others occupying wholly different segments of my life - their order and relation attested only in the fragile record of my phone's photo reel. I was morbidly aware of the risks of this approach - so aware that I spent many of my dreams fumbling with shifting camera apps, terrified of missing a photo of some brief roadside vision. And yet when the phone finally succumbed to light rain on Christmas morning, after surviving theft on the Piccadilly Line and half a dozen falls into the ocean, and all 35,000 photos were totally, irrevocably gone, I felt less distraught than unburdened.

I was unaware that Luxi, in a typically brazen act of competence, had taken the phone some years before and quietly turned on automatic backups. The whole pile now sits in quiet disarray on a Google server, shuffled and duplicated and then shuffled again by a failed cloud migration and my clumsy efforts to impose order: present, mercilessly safe, but a mess beyond redemption.

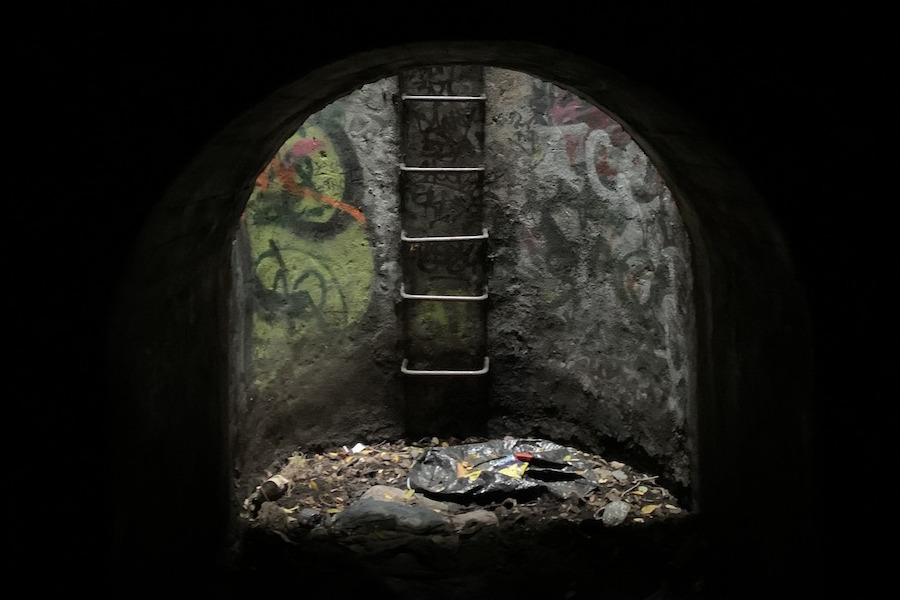

It's been two years and I've rarely had the stomach to look at them. When I do, I find road trips dismembered and rearranged: sequences of blurry landscapes taken through the windows of different sedans. You develop tricks to place them. Tree species, the color and width of the lane markings, snatches of language on distant signs all become important. The timestamps in the metadata are distorted by blatant lies - picturing me in 1995, the year of my birth, already towering and haggard beside a Suburban in completely anonymous desert. There are dozens of claustrophobic midnight scenes, back-seat nests in rest stops that will remain forever unnamed. In their haphazard way the pictures reflect that period more accurately than anything I could write here. In memory the drives have nearly fused, less separate events than a parallel mode I sometimes entered.

I’ve felt devoted to these photos for years like some doomed curator, but I don’t think I ever liked them. Photography doesn’t really interest me. Each one is a committed lie: a promise that someday I'd do something to commemorate that first sensation. Let me show you a few first, without commentary.

At some point, each one seemed instrumental to a piece of writing that would resolve everything. But by then I was already living too quickly for that to have happened. I was moving between installments of what Luxi took to calling the "death drive", capturing an insidious logic that emerges a few hours into the road trance when the white heat of movement takes hold and you find yourself calculating the farthest point you can reach in the brief tenure of the rental car. There is a perverse necessity to traverse as much of a country as possible, missing every Lonely Planet highlight, and seeing only one distant thing with incredible brief clarity. Ten minutes in Bar Harbor in a blizzard. A few hours at the visitor center of the Shiretoko Peninsula. Pitiless nights huddled under sodden driftwood on the southern coast of Sweden. I would find these places - first by chance, and then again and again in the years that followed, returning obsessively whenever I could - rarely seeing anything new in a country, drawn only to taste again of some sensation so specific that I had craved it for years.

I would be on the fell southern banks of the Danube one night, looking back at Bratislava as Ortiz read aloud and swirled the trash among the root-bound shallows with his boot - and on top of a ridge in the White Mountains the next, tending an oily fire of the Park Service's rarest and most precious pine needles as Pusic burned too with his own sheer Protestant exuberance. My passengers would model completely opposed understandings of what we were up to - but the proximity of the encounters made for absurd lapses. Driving beside them at night, I would sometimes look over and find that I had gotten them confused.

You recall other details with an absolute, useless clarity. How a homeless woman standing on the shoulder of the I-95 outside of Bridgeport, Connecticut stared across 30 feet of grey air into the windows of an empty glass factory in a state of full-body rapture. Or how it feels to fall from the trance of the Peak District straight into Sheffield on Ecclesall Road: skidding down a chute of homes that flash from mock Tudor to pebbledash like pictures in a zoetrope. There were whole afternoons when towns in the Midlands seemed the answer, or one answer, already fragile, a potential route forward occluded by a thick pane of glass. The briefest glimpse of an ideal valley has you exiting the freeway only to find slumping rows of brick barracks and cottage-cheese stucco, all of it hanging like a miasmic gel over the hills that formed the locus of your intense longing. These discoveries drove me to constant frustrated movement, an aimless grappling with the finite number of ways you can relate to a certain view, the limited roles available to you in a foreign country's villages.

When I did stop (and stopping isn't easy at this pace: you realize that the brakes fell off a hundred yards back, that spiritual momentum is as real as physical) there seemed to be some unified theory hovering above it all, some pattern or cipher that would make apparent the role that this series of revelations would play in my life.

So I would return to the few cities where I was missed and try to make a version of myself legible. When asked how I'd spent the last five years, I realized that I had at once far too much and far too little to say. It helped that outwardly similar lifestyles had become popular while I was gone. Among the people I'd met in college, I could think of a dozen pursuing similar itineraries - but keyed to the numerical outcomes of philanthropy or the scale of SaaS start-ups built in Morroccan coffee shops. The whole thing made coherent by a commitment to some verbose and monolithic value structure. When I stayed with these people's parents - leaning around pyramids of organic produce to make eye contact in dazzlingly lit kitchens - they would reframe what I was doing in the terminology of their children's lives: all of the "optionality", none of the "impact". For my own parents, my passport alone was an object of wonder; looking at its stamps together was among the most uncomplicated joys that the travel offered.

Then the logistical captors I'd almost forgotten I was fleeing would begin to close in, demanding the periods of frantic industry that kept the whole taped-together machine creaking forward: the rental cars booked and promises made, the scattered sham labor sent off. Already many others I knew were prematurely winding down, scheduling a half-day's recreation two months in advance. As much as anything, I was running from them. In some immature, anarchic way I was proud of this - proud that I was living at a pace that I knew most others couldn't, proud too that I had evaded nearly every external system, every form of constraint. All enabled by the perverse conditions of contemporary life: that all of this is cheaper than sitting still. If you know what you're doing, it's essentially free.

And then sometimes a photo swims up from the pile and is entirely self sufficient. It pulls you straight back in.

Wool socks dry on the dashboard. Above, framed in the vanishing arcs of the wiper blades, a series of images appear in miniature before being erased by snow: a weathervane shaped like a leaping horse, derelict bobcat diggers arranged in conspiratorial semicircles, a gazebo slumped in a century's slow fall. Pittsfield, Maine has one open business and it's Vittles, where siblings Rick and Irma skid around on feet as thin and elongated as canoes. Modeling essentially identical bodies, an inheritance in the truest sense, their thorax and rib cage are articulated back between their high sloping shoulders, suggesting a carapace concealed under his battered rain coat, her mottled fuschia jumper. In one perfect gesture, Irma approaches our table, spins a chair around, and straddles it to take our order. When she removes her knit cap, a bob of obsidian hair falls and bounces up from her shoulders with the lively abstraction of a stop motion film. As our omelettes cook, Rick steps outside to clear the snow from the stoop and slides three feet backwards with each desperate destabilizing stab of the shovel. In their own way, skittering around under the crumbling vinyl ceilings, advancing a dialogue that has continued unbroken since their birth ("I was out first!" Irma whispers, wide-eyed), they are the most charismatic people I have met in years. They are minor nobility in exile from a country I have visited only once in a dream.

That's one more clue; jot it down. The too-powerful metaphors of childhood given complete control: the detective's notepad, a side-quest's checklist superimposed over the world, the Aleph in Carlos Argentino Daneri's cellar. All of it simultaneous and coeternal, attenuating evenly out of meaning as the photos swell beyond any possible usefulness, defying the inferences they seem to make possible. There is constant reflection and yet none at all. None of it can possibly be instrumentalized. The mental catalogue simply growing, the map filling in. Any doubt beaten by the certainty that if only I returned once more to that stretch of agricultural highway where I first felt some atmospheric potential - then it would all come together.

On December 18th, in the Sunken Gardens of the Santa Barbara Court House, beside a bush where I found a dead man as a child, I married the only person who has kept up; the only person who, on the announcement of a lockdown in London, looked at someone she'd known for two weeks and said something entirely at odds with her upbringing and national character: "Let's get out of here."

We were in Istanbul within days, walking through a stunned and silent city as we realized, the first of many times over the next four years, the extremity of what we had agreed to. We rented a few cars each month, never signed a lease, never compromised; we constantly looked back.

I am no longer on shore leave. My daily tasks are flyering hilltop neighborhoods with promises of increasingly vague services, or trying to convince a 60 year old man that I can afford his spare bedroom. For the next few months at least there will only be memories, heavily romanticized - ways of looking back at a previous life that already feels like it's drifting slowly away.

Last week I took the ferry to Vallejo and bought an '02 Camry from a man by the docks. It's mithril blue with black leather, an early GPS that shows highways a single pixel wide slashing out across a black expanse. There are some new roads out there that my dad told me about: stretches along the river delta that go completely dark at night. I think I’m going to delete the photos.