Summer in the Kingdom II

2023 · 11 · 11

Somewhere out in the dusty void between The Zone and U Walk, Syed and I found ourselves thinking of the mountains. I spoke of the holiness of the Pine Marten Bar after coming down from the Cairngorm Plateau; he raised his much more impressive expeditions into Kashmir. Driven to escapism by the midnight heat, we soon reached his final climb—when, hanging from an ice axe at 7000 meters, he had looked up to watch a buttress collapse and was somehow carried half a kilometer on top of the avalanche but never buried. By the time he managed to self arrest, two of his close friends had died under the snow. We shared an odd serenity as he related all of this—how he had then started a family, moved to England to pursue his PhD, and used the stipend to open a rural school back home.

At some point during this story we decided to drive into the desert, and the next day we were at the airport trying to rent a car. The man at the counter needed a confirmation number starting with a 1 or a 6; ours started with a 9—an impasse I seem to face constantly, always ending in that familiar state of negotiations abroad where the same English statements are repeated by both sides in louder and rapidly darkening tones. Then Syed said something in Urdu and suddenly backs were being slapped and the number no longer mattered, the man winking as he informed us that a further scam would now also be abandoned.

One fine point of Saudi humor is the placement of unmarked speed bumps on the freeway, which offer two feet of air at the least expected moments. The suspension was in rough shape by the time we reached the unmarked road leading off the highway, but Syed and I had achieved a degree of levity unknown for weeks.

The key to off-roading a rented sedan is to make the moment of paying the deposit as painful as possible and then to wipe the existence of that money from your mind. It was never yours. Once you are fully resolved to financial ruin, gunning whatever Corolla or Yaris you have been given over boulders and down dry river beds becomes purely rational: the extraction of maximum value from your investment.

An hour later, we ran the car up onto an embankment from which it would not descend and left it sitting there at a sickly angle, the passenger side wheels spinning inconsolably. Syed spotted a low outcropping on the horizon, so we climbed to the top and found the ruined foundations of an old settlement. Below us in the valley, a small cluster of huts were the only thing visible for miles. A Bedouin family began the call to prayer and their herd of black camels responded, crowding around the father's Tacoma.

Syed prayed on the cliff's edge while I walked out and looked at a line of violent amber spreading from the horizon. I called back over my shoulder "I think I can see the Edge of the World out there" and much later, as the last of the color failed and the small village grew too grainy to see, Syed rose from his prayers and replied "This is the edge of the world for us, my friend." And he was right—so we climbed back down the hill and managed to roll the car onto level ground in time for a complete darkness to descend.

We were quickly lost, our high beams showcasing different swaths of identical sand. The way the light sliced out into it and encountered nothing lent our small cab a sense of immersion—of movement through a viscous medium, as claustrophobic as footage from a deep sea expedition. Then, in what seemed at first a hallucination, Syed pointed to two small points of light dangling out in the depths. They wobbled slightly, turned to face us, grew. We sat still, entranced by expectation—until, like the arrival of a messenger from a different realm, a sedan rolled to a stop beside us. A local leaned out of the window with a frantic gleam in his eye and shouted, "We go to the Edge of the World!"

Syed shook his head. "Brother, the road's no good."

Then the back window rolled down to reveal a twitchy German with a face the size of a dinner plate.

"Do you hear? He sayz ze road iz very bad."

The local cackled and roared "We are better, inshallah" and they shot off past us.

A few minutes later they were back, falling in behind us to form a caravan of the defeated. We led for a while, running over bony shrubs that pulled at the undercarriage like fingernails—then breaking free for long stretches to speed out blindly into the night, signaling to each other across the valley floor with our turn indicators in pure elation. Eventually we found the highway and parted ways, stopping only once more that night so Syed could haggle with some Sudanese guys crouching around an air compressor to blow the remnants of the desert out of our engine.

All told, it was five hours out and back: an exceedingly clean failure, and Syed a steadier hand than any I'd driven with abroad. So we tried it again with a few others a week later. During another crisis at the rental car counter, the female manager walked into the back room where her male coworkers couldn’t see and stared at me as she slowly removed the veil from her niqab. We both stood completely still for a moment, and then she put it back on and went about the paperwork as if nothing had happened. After three weeks in Saudi, this gesture felt like an epiphany, although I had no idea what it meant. She gave us an Expedition, the sort of vehicle I associate with the ATF or deep Maryland, and soon we’d joined a long convoy of Suburbans and Land Rovers, flying over the same creek beds that had nearly capsized us a week before.

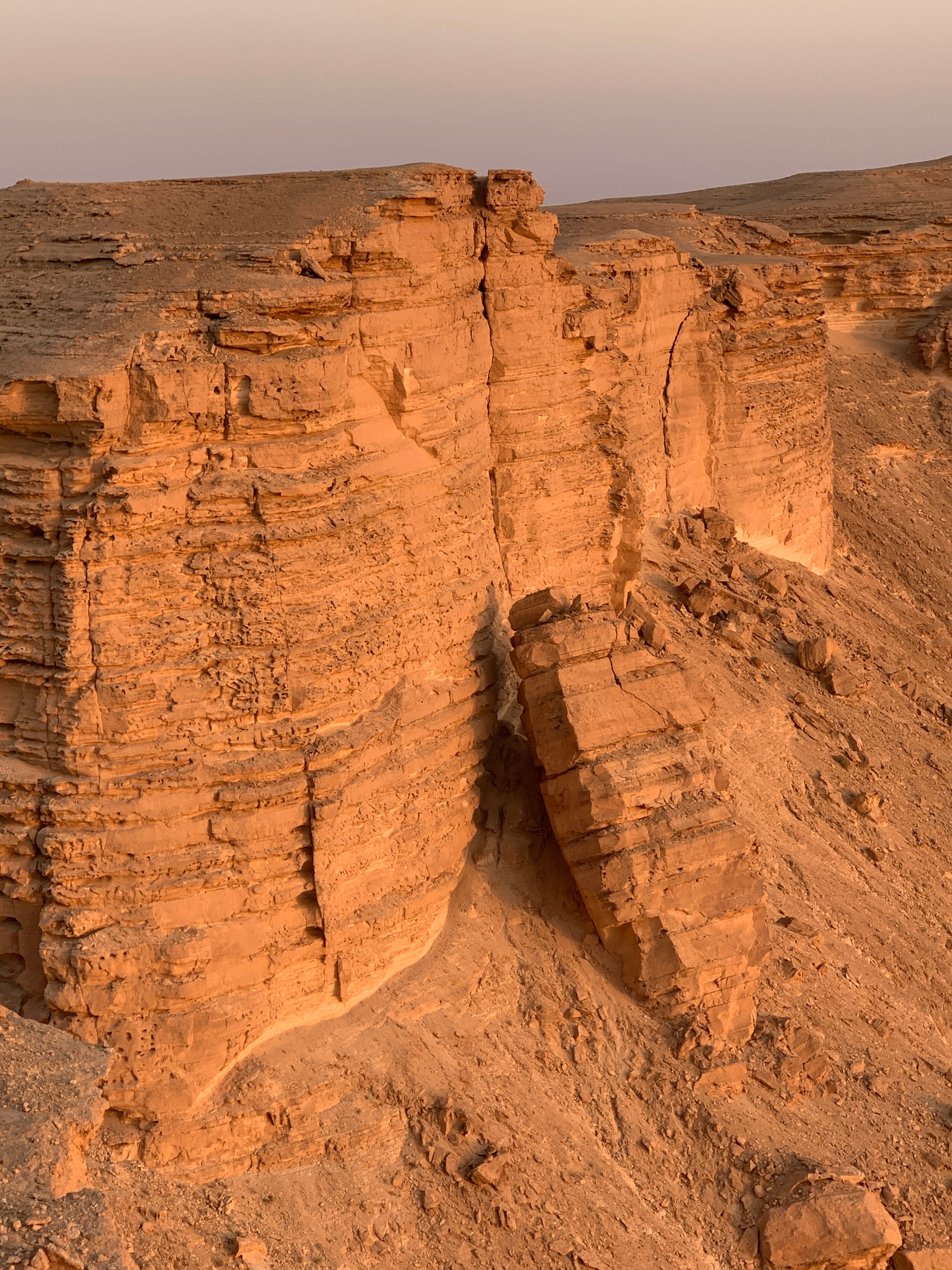

At the Edge of the World, Chinese tourists squatted and smoked, facing away from the view. We climbed a series of rolling peaks over a clean thousand foot drop, the wall rippling across the valley like gold ribbon. There was something disorienting about how the sand piled against the cliff’s face, recalling coastal erosion and the cries of seagulls. Buttresses with the symmetrical grooves of a lathe stood frozen in time, caught partway through their slow collapse.

Night fell. Someone offered a treatise on the physics of satellite design, and we all lay for an hour with our feet hanging off the edge. Behind us the guided tour groups ate on carpets thrown over the sand, their Suburbans circled up like wagons. Eventually we followed a truck back out through the desert and drove across Riyadh in search of softer sand.

We found it 40 miles southeast of the city, where a hole had been blown in a sandstone mesa and eight lanes dropped into a deep valley. At the bottom we pulled off and spent a few fitful hours in the car, soon giving up to hike out into the dunes. The sand was like pastry flour sifted into incredibly precise ridges, elsewhere corrugated with the patterns of the wind.

Around 4am, the season's first breeze kicked up, and I got to enjoy an hour of 80 degrees, the coolest temperature I'd felt in a month, which I passed marveling at the density of human interest available anywhere. Some things I saw from my sleepless vigil on the side of a dune:

- A man pulled off the highway in a sedan, dove into the pool of light cast by his headlamps, and threw a handful of sand into the air, watching it fall through the beams. Satisfied, he got back into the car and drove off up the hill. Seeing things like this occur in a country without alcohol makes them all the more powerful, suggestive of a truly crazed ecstasy.

- Across the freeway at the valley's lowest point was the largest thicket of trees I saw in Saudi—a wall of them surrounding a compound, completely impenetrable by night. Dozens of dogs barked at one another inside until just before dawn, when a man driving past sneezed so loudly out of his window that all the dogs fell silent.

- The same super car roared down and then up the grade multiple times as if trying to make a point to the desert, prompting Syed to murmur "always more boy racers" in his sleep.

- Meanwhile, a lifted Tacoma across the highway fared worse: driving up and sliding back down the same dune, trying desperately to reach his friend's identical truck on the peak. Each time he failed, he would reverse farther out into the freeway to gather momentum before rocketing back up, spraying great waves of sand behind him, and stalling. When he finally made it to the top, he stepped out into the other truck's headlamps and embraced the driver.

At dawn we found a smoggy swap meet near the road and rented quads until the heat became unbearable.

The final week passed in a haze of tours. I was shown Digital City, like the sun-dried husk of some vast quartered fruit, its core scooped away to reveal a spare courtyard of palms and polished cement. Eating my first good salad in weeks in the canteen, I was surrounded by scalded Brits balding in exile—dozens of them, and more joining all the time, their rubber soles squeaking as they jogged between patches of shade. Wearing badges with titles like "Managing Director, Terraforming", they were restored to wry smiles and self effacement by the air conditioning, making them seem less expats than anachronisms, men sent through time to take up symbolic advisory roles.

We were driven to the NEOM Experience, a compound of white hangars built to advertise the linear city.

A young man, one of those Saudis who look and sound like no race you've seen before, had drawn the short straw and was pushed forward to be our guide. Petrified, he moved us and the camera crews swiftly between an endless series of rooms, each filled with architectural models the size of playgrounds. He kept saying "I don't want to rush you" and then urging us along, as if it were crucial that we didn't look too closely at anything.

One of the professors tapped a piece of frosted blue plexiglass. "Why is it upside down?"

"It is made of ice. And it spins. Let's move on to the next room. Please tell me if I'm rushing you."

Someone said, "You're rushing us."

"I'm sorry." He grimaced and jogged to the next room, where he gestured at some minute figures twirling in a column of glass. "The Ministry of Culture will hold dance classes in these pillars. All halal." It was a joke, but he looked close to vomiting.

Syed seemed to settle the matter when he put his hand on the guide’s shoulder and pointed to some little figures scaling a floating island. "Brother, are you saying this is real?"

And of course we saw Riyadh’s glory, The Boulevard: a 220 acre phantom of Times Square. It was completely unclassifiable, a city in its own right—a place where, after a TSA pat-down, you were guided along paths sprayed with mist and sold fast food while e-sports played on enormous screens. There was an attempt at a rave, but even when the DJ tried to show the crowd how to move their arms, not a single person danced. There was a "Hangul Pavilion" where girls with frost-blue contact lenses under their niqabs bowed and let out a long chorus of “anyeonghaseyo”. Something about the dry heat and the dryer air conditioning had forced my perceptive core deep back into my head. It felt as if I were encountering all of this through the shadows and echoes it sent down the inflamed corridors of my nostrils.

A gaunt cartoonish Russian stood outside the e-sports arena, smoking in the 95 degree night, the collar of his white polo shirt turned up against the neon. I looked up and saw his face blown up to 40 feet on the wall of the stadium: his arms crossed, a sparkle effect added to his eyes. Fergus asked him how the competition was going. "I dropped in the first round." He paused for a long time and watched the people walking along the Boulevard, and as we left him to his misery I heard him say softly, "How easily it all falls away, and then you wake up in this shithole."

On the way back, our driver gave a detailed speech about youtube. ("The Faze Clan is totally corrupt, soon banned inshallah, no goal, only money. I watch them, yes.") When this dried up, he started waving his phone around the cab—his photo reel another unending slab of neon videos, all meals out at Western fast food chains, the audio for each cutting in and out on the car's speakers to compete with his music. He missed the turn onto campus three times and eventually threw on his hazards to back up along the freeway.

That night they rolled out some rugs on the roof and we kneeled around enormous plates of lamb soaked in honey. With our departure looming, a tone of real frivolity emerged in our little outpost of air conditioning over the desert—an auctioneer-style addressing of the topics forbidden at home. As the cab pulled away from the Boulevard, Fergus had commented that it all felt like the metaverse, and I knew exactly what he meant: that Riyadh felt less like a place than a series of references, a city haunted by other cities and yet entirely immune to their judgement. And with that surrealism came an indulgent break from certain premises: from the stifling ubiquity of an anxious puritanism in the West, a fear of anything that might impart the stain or odor of corruption. I’ve met many abroad who are addicted to this form of freedom; I stayed adrift for many years partly to cling to it myself. But for its brief compensations, it’s almost always a trap, a poor substitute for simply enjoying the desert and then passing-by.

As we walked into the closing ceremony the following morning, we were greeted with the applause of our 200 young men, their parents, and rows of minor dignitaries—our own ranks decimated by a poisonous plate of honeyed lamb. After an agonizing speech by the stuttering provost, we were shown a film of ourselves: our classes edited into action sequences, our routines narrativized to match government KPIs. The music swelled. An Arabic voiceover announced our valor. Every man associated with the university was brought onstage to accept an award. We signed the kids' thawbs, shook hands with their fathers, averted our eyes from their mothers, and drove to the airport.